Humanity’s effect on the environment often is framed in the context of the post-industrial era, but new archaeological research reveals how intensive land use by a medieval East African population altered their African island’s environment forever.

Unguja Ukuu, an archaeological settlement located on the Zanzibar Archipelago in Tanzania, was a key port of trade in the Indian Ocean by the First Millennium when the island was populated by farming societies establishing trade links toward the Indian Ocean, China, and beyond.

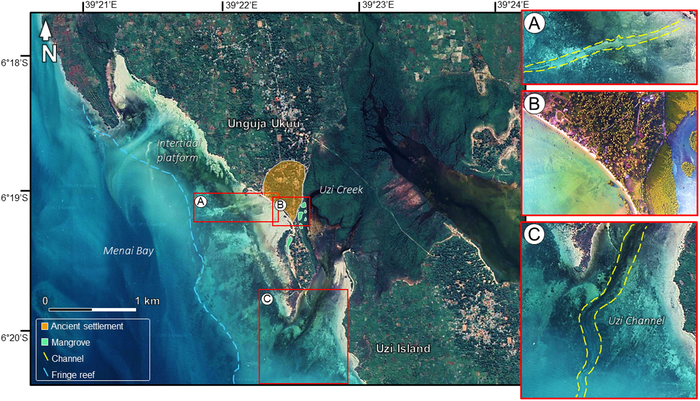

A new study “Coastal landscape changes at Unguja Ukuu, Zanzibar: Contextualizing the archaeology of an early Islamic port of trade” published in the Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology describes how human activities modified the shoreline at Unguja Ukuu.

Urban growth at the coastal settlements and trade ports on the island, and associated trade activities may have silted up the lagoon hindering the sea traffic and ultimately affecting fish numbers and played part in the community’s decline.

African island’s environment

For millennia, the Indian Ocean was the maritime setting for a budding form of globalization, with extensive trade and exchange networks operating between eastern Africa, Southern Arabia, and Southeast Asia, which foreshadowed modern global shipping networks.

“The islands of the Zanzibar Archipelago witnessed numerous environmental and cultural changes as the region became a hub of maritime trade, cross-cultural interaction, and global exchange,” said the study’s lead author and Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at Flinders University, Dr. Ania Kotarba–Morley.

These changes resulted in the dumping of food remains, general waste, and increased agricultural activity and land use, all of which negatively impacted sediment build-up along the island,” said a senior author of the study, Associate Professor Mike Morley of Flinders University.

While discussion about humans affecting the planet and its natural environments is ever-present in our current discourse, it almost always refers to the modern role and is focused on agricultural or urban areas such as large cities.

The study outlines how human interference in a natural environment affected coastal landforms and sediments on a remote East African island over 1,000 years ago and directly changed the fortunes of the coastal inhabitants in the area as a result.

As part of recent archaeological excavations aimed at understanding the site’s transregional trade networks, geoarchaeological analyses were undertaken to document the geomorphic context of the ancient settlement.

Excavations show stratigraphy

Unguja Ukuu’s deep coastal stratigraphy appears to record the progradation of an inhabited back-reef shore from the mid-7th to the 9th Centuries AD, perhaps in the wake of an earlier middle to late Holocene marine transgression. Excavations on the back-beach show that deposits associated with the ancient settlement include interlayered middens, and backshore sands and, in later phases, a peri-urban dump with dark-earth-type anthrosols developed on these deposits.

Coastal progradation appears to have been driven in part by the accumulation of anthropogenic detritus and compaction of ancient surfaces. The authors hypothesize how the inherited, submerged relic Late Pleistocene geomorphology of the intertidal zone and later Holocene sediment supply from the hinterland may have supported the emergence of Unguja Ukuu as a trading locale, and possibly contributed to its decline in the early second millennium AD.

“To help understand how and why these ancient ports thrived or declined, it is important to know how the coastal landscape influenced the way traders undertook their commercial activities, or drove decisions, including mooring locations, investments of labor, and capital by local communities and any central authorities.

“From an environmental standpoint, it is crucial to know whether this commercialization had a physical effect on the coastline, anthropogenically modifying the landscape morphology or causing change,” said Dr. Kotarba-Morley

The researchers say these processes might be implicated in the decline, and eventual abandonment of Unguja Ukuu at the turn of the second millennium AD—a period of regional socio-political and economic transformation of coastal African societies that marked the emergence of maritime Swahili culture.

The study’s authors are Kotarba-Morley, Nikos Kourampas, Morley, Conor MacAdams, Alison Crowther, Patrick Faulkner, Mark Horton, and Nicole Boivin.